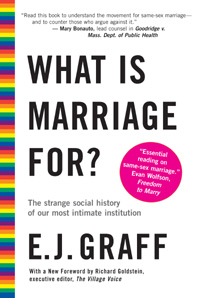

It is an historic day for marriage equality in the United States. The Supreme Court decision in US v. Windsor struck down the Defense of Marriage Act; and the more limited ruling in Hollingsworth v. Perry effectively moots Prop. 8 in California. Beacon has been publishing books that promote valuing all families, including but not only through marriage equality, for a long time. Take, for instance, What is Marriage For? by E. J. Graff, which we first published in 1999, and is considered by many "the bible of the same-sex marriage movement."

This excerpt from What is Marriage For? explores that public/private intersection of our definition of marriage. We hope that this book continues to inspire people to fight for LGBT equality across the country and around the world.

In honor of Pride, we're giving a special discount of 25% off What is Marriage For? and all other LGBT titles at Beacon.org on orders using the Promo Code PRIDE placed during the month of June.

Inside Out or Outside In: Who Says You’re Married?

Inside Out or Outside In: Who Says You’re Married?

One of the most basic tensions in the history of marriage is between those two interlocking sides of marriage: marriage as a publicly policed institution and marriage as an inner experience.

Which one turns your bond into a marriage: a public authority or

your heart? Are you married when the two of you decide to care for

each other for life, a decision you live out day to day, a decision only

afterwards recognized by your community? Or is it the other way

around: does the family, or church, or state pronounce some words

over your head, write your names side by side in a registry, and bestow upon you a marriage, a license and legal obligation to carry

out the responsibilities of a¤ection and care? This may sound like

one of those faces/vases illusions, and for good reason: marriage

doesn’t exist unless both parts happen—two human beings behave as married, and everyone else treats them as such. But it does

matter which side you think counts more: the decisions made

about individual marriages will be quite different if you think marriage is a publicly conferred status or an immanent state. And each position’s internal contradictions can—and have—caused social

havoc when unchecked.

In history, this debate is almost inextricable from the debate

over which authority rules marriage. Who decides where the enforceable marriage is made—in your heart, or in a registry—and

why? That decision might be less complex if the only people who

have to recognize your marriage live within twenty-five miles,

when the people who see you two behaving as married are also the

ones who oversee the granting of the widow’s dower. And it might

be more complex in our world, in which each of our daily lives goes

beyond our circle of acquaintances to touch dozens of strangers

and anonymous entities, from the motor vehicles registry to our

children’s schools. The story of the public/private marriage line is

therefore also a story of how marriage has shifted, in comparative

legal scholar Mary Ann Glendon’s words, from custom to law.

Roman marriage was the immanent kind: when challenged in

court (over, say, whether a widow inherits or whether a child is legitimate), a marriage could not be proved by anything so simple as

a public registry. A judge had to investigate whether the two lived

together with affectio maritalis, ‘‘the intention of being married.’’

To be married, all a couple had to do was ‘‘regard each other as man

and wife and behave accordingly.’’ What does that mean, ‘‘behave

accordingly’’? The Romans may never have defined it, but (like

Americans and pornography) they knew it when they saw it. A

judge sized up the couple’s ‘‘marital intentions’’ by such signals

as whether she’d brought a dowry, or whether he openly called her

his wife. Augustine and his concubine, for instance, were living

together without affectio maritalis, since he was intending a later

power-marriage. But had the same pair intended to be married—with no change in their behavior—they would have been. Marriage

was a private affair: the state could police only the consequences,

not the act.

While the Jewish configuration changed over the millennia,

what remained central is marriage as a private act: only bride and

groom could say the magic words that turned them into husband

and wife. After many centuries the rabbis inserted themselves and their seven blessings into the ceremony, before the big feast, but

even they knew they were not essential: the pair made the marriage

within themselves. Which is why, in Jewish law, a court could neither ‘‘grant’’ nor refuse a divorce. If a husband’s inner willingness

to be married evaporated (sometimes hers counted but often it did

not), then the marriage itself had evaporated: the rabbinical court

or bet din could merely decide questions of fault and finances.

Christianity, as we know, wanted nothing to do with marriage

for centuries. When asked, some priests might come by and say a

blessing as a favor, just as they’d say a blessing over a child’s first

haircut. No one considered marriage sacred, as celibacy was: marriage was one of those secular and earthbound forms rendered

unto Caesar. But as centuries rolled by, an increasingly powerful

Church saw that marriage was central to ordering Europe’s civil

and political life—not so much those few called to sainthood, sacrifice, and martyrdom, but the many ordinary folk who needed to be

told how to behave.

And so the Church launched a battle for power over marriage’s

rules, a battle that lasted roughly a thousand years. Today we have

the peculiar impression that Catholicism has always had one vision of marriage, but for every marriage rule eventually imposed

on Europe, the Church’s own debates were abundant. It first formally ruled on marriage in 774, when one pope handed Charlemagne a set of writings that defined legitimate marriage and

condemned all deviations. After another five hundred years of

struggle, the Church came up with a marriage liturgy and imposed

its new and radical rules—the ballooning incest rules, the one-man-one-marriage rule, and most controversial, the girl-must-consent rule—on the powerful clans. ‘‘It is clear,’’ writes one historian, ‘‘that this attempt to impose order on matrimonial practice

was part of a more ambitious plan to reform the entire social order. . . . regulating the framework of lay society, from baptisms

to funerals,’’ the most intimate acts of most people’s lives. The

Church’s push to rule marriage was slow and uneven but very determined. Here and there it would issue a decree and struggle with

local nobles over whether it would be observed; now it would retract a bit to permit a lord to marry his dead wife’s sister or annul

his existing marriage; then it would push forward again.

It was not until 1215 that the Church finally decreed marriage a

sacrament—the least important one, but a sacrament nonetheless—and set up a systematic canon law of marriage, with a system

of ecclesiastical courts to enforce it—and had a fair amount

of people willing to observe those rules. By 1215, the year that

the Fourth Lateran Council issued its matrimonial decrees, the

Church had ‘‘broke[n] the back of aristocratic resistance . . . after

lengthy individual battles with the nobility, kings included.’’

And according to the Church, what turned two individuals into

a married couple? It was—drumroll, please—the couple’s private

vows.

Why a drumroll? Because the Church insisted that a private

promise was an unbreakable sacrament—that marriage was an immanent experience, a spiritual reality created by the pair’s free and

equal consent. That was practically a declaration of war against the

upper classes, a radical and subversive idea emphasizing the sacredness of the individual spirit. Marriage, the Church insisted,

was not just about land and power and wombs, but about human

feelings.

Read the rest of "Inside Out or Outside In: Who Says Your Married?" at SCRIBD.

What Is Marriage For?: The Strange Social History of Our Most Intimate Institution by EJ Graff by Beacon Press