By Martin Luther King, Jr.

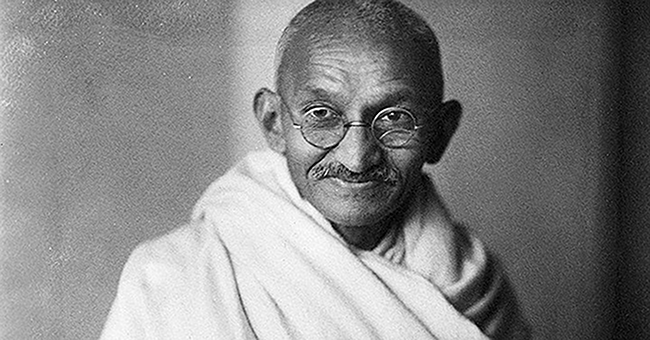

Studio photograph of Mahatma Gandhi, London, 1931.

For Martin Luther King, Jr., Gandhi embodied the spirit and ethos of Christ. On the anniversary of the passing of India’s nonviolent, anti-colonial revolutionary, we look at highlights from the Palm Sunday sermon, delivered on March 22, 1959, at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, Dr. King wrote on him.

***

This, as you know, is what has traditionally been known in the Christian church as Palm Sunday. And ordinarily the preacher is expected to preach a sermon on the Lordship or the Kingship of Christ—the triumphal entry, or something that relates to this great event as Jesus entered Jerusalem, for it was after this that Jesus was crucified. And I remember, the other day, at about seven or eight days ago, standing on the Mount of Olives and looking across just a few feet and noticing that gate that still stands there in Jerusalem, and through which Christ passed into Jerusalem, into the old city. The ruins of that gate stand there, and one feels the sense of Christ’s mission as he looks at the gate. And he looks at Jerusalem, and he sees what could take place in such a setting. And you notice there also the spot where the temple stood, and it was here that Jesus passed and he went into the temple and ran the money-changers out.

And so that, if I talked about that this morning, I could talk about it not only from what the Bible says but from personal experience, first-hand experience. But I beg of you to indulge me this morning to talk about the life of a man who lived in India. And I think I’m justified in doing this because I believe this man, more than anybody else in the modern world, caught the spirit of Jesus Christ and lived it more completely in his life. His name was Gandhi, Mohandas K. Gandhi. And after he lived a few years, the poet Tagore, who lived in India, gave him another name: “Mahatma,” the great soul. And we know him as Mahatma Gandhi.

~~~

I would say the first thing that we must see about this life is that Mahatma Gandhi was able to achieve for his people independence through nonviolent means. I think you should underscore this. He was able to achieve for his people independence from the domination of the British Empire without lifting one gun or without uttering one curse word. He did it with the spirit of Jesus Christ in his heart and the love of God, and this was all he had. He had no weapons. He had no army, in terms of military might. And yet he was able to achieve independence from the largest empire in the history of this world without picking up a gun or without any ammunition.

Gandhi was born in India in a little place called Porbandar, down almost in central India. And he had seen the conditions of this country. India had been under the domination of the British Empire for many years. And under the domination of the British Empire, the people of India suffered all types of exploitation. And you think about the fact that while Britain was in India, that out of a population of four hundred million people, more than three hundred and sixty-five million of these people made less than fifty dollars a year. And more than half of this had to be spent for taxes.

Gandhi looked at all of this. He looked at his people as they lived in ghettos and hovels and as they lived out on the streets, many of them. And even today, after being exploited so many years, they haven’t been able to solve those problems. For we landed in Bombay, India, and I never will forget it, that night. We got up early in the morning to take a plane for Delhi. And as we rode out to the airport we looked out on the street and saw people sleeping out on the sidewalks and out in the streets, and everywhere we went to. Walk through the train station, and you can’t hardly get to the train, because people are sleeping on the platforms of the train station. No homes to live in. In Bombay, India, where they have a population of three million people, five hundred thousand of these people sleep on the streets at night. Nowhere to sleep, no homes to live in, making no more than fifteen or twenty dollars a year or even less than that.

And this was the exploitation that Mahatma Gandhi noticed years ago. And even more than that, these people were humiliated and embarrassed and segregated in their own land. There were places that the Indian people could not even go in their own land. The British had come in there and set up clubs and other places and even hotels where Indians couldn’t even enter in their own land. Gandhi looked at all of this, and as a young lawyer, after he had just left England and gotten his law—received his law training, he went over to South Africa. And there he saw in South Africa, and Indians were even exploited there.

~~~

You have read of the Salt March, which was a very significant thing in the Indian struggle. And this demonstrates how Gandhi used this method of nonviolence and how he would mobilize his people and galvanize the whole of the nation to bring about victory. In India, the British people had come to the point where they were charging the Indian people a tax on all of the salt, and they would not allow them even to make their own salt from all of the salt seas around the country. They couldn’t touch it; it was against the law. And Gandhi got all of the people of India to see the injustice of this. And he decided one day that they would march from Ahmadabad down to a place called Dandi.

He was able to mobilize and galvanize more people than, in his lifetime, than any other person in the history of this world. And just with a little love in his heart and understanding goodwill and a refusal to cooperate with an evil law, he was able to break the backbone of the British Empire. And this, I think, is one of the most significant things that has ever happened in the history of the world, and more than three hundred and ninety million people achieved their freedom. And they achieved it nonviolently when a man refused to follow the way of hate, and he refused to follow the way of violence, and only decided to follow the way of love and understanding goodwill and refused to cooperate with any system of evil.

~~~

He had the amazing capacity, the amazing capacity for internal criticism. Most others have the amazing capacity for external criticism. We can always see the evil in others; we can always see the evil in our oppressors. But Gandhi had the amazing capacity to see not only the splinter in his opponent’s eye but also the planks in his own eye and the eye of his people. He had the amazing capacity for self-criticism. And this was true in his individual life; it was true in his family life; and it was true in his people’s life. He not only criticized the British Empire, but he criticized his own people when they needed it, and he criticized himself when he needed it.

And whenever he made a mistake, he confessed it publicly. Here was a man who would say to his people, “I’m not perfect. I’m not infallible. I don’t want you to start a religion around me. I’m not a god.” And I’m convinced that today there would be a religion around Gandhi if Gandhi had not insisted all through his life that “I don’t want a religion around me because I’m too human. I’m too fallible. Never think that I’m infallible.”

~~~

Now you know in India you have what is known as the caste system, and that existed for years. And there were those people who were the outcasts, some seventy million of them. They were called untouchables. And these were the people who were exploited, and they were trampled over even by the Indian people themselves. And Gandhi looked at this system. Gandhi couldn’t stand this system, and he looked at his people, and he said, “Now, you have selected me and you’ve asked me to free you from the political domination and the economic exploitation inflicted upon you by Britain. And here you are trampling over and exploiting seventy million of your brothers.” And he decided that he would not ever adjust to that system and that he would speak against it and stand up against it the rest of his life.

~~~

And he looked at all of this. One day he said, “Beginning on the twenty-first of September at twelve o’clock, I will refuse to eat. And I will not eat any more until the leaders of the caste system will come to me with the leaders of the untouchables and say that there will be an end to untouchability. And I will not eat any more until the Hindu temples of India will open their doors to the untouchables.” And he refused to eat. And days passed. Nothing happened. Finally, when Gandhi was about to breathe his last, breathe his last breath and his body—it was all but gone and he had lost many pounds. A group came to him. A group from the untouchables and a group from the Brahmin caste came to him and signed a statement saying that we will no longer adhere to the caste system and to untouchability. And the priests of the temple came to him and said now the temple will be open unto the untouchables. And that afternoon, untouchables from all over India went into the temples, and all of these thousands and millions of people put their arms around the Brahmins and peoples of other castes. Hundreds and millions of people who had never touched each other for two thousand years were now singing and praising God together. And this was the great contribution that Mahatma Gandhi brought about.

And today in India, untouchability is a crime punishable by the law. And if anybody practices untouchability, he can be put in prison for as long as three years. And as one political leader said to me, “You cannot find in India one hundred people today who would sign the public statement endorsing untouchability.” Here was a man who had the amazing capacity for internal criticism to the point that he saw the shortcomings of his own people. And he was just as firm against doing something about that as he was about doing away with the exploitation of the British Empire. And this is what makes him one of the great men of history.

And the final thing that I would like to say to you this morning is that the world doesn’t like people like Gandhi. That’s strange, isn’t it? They don’t like people like Christ. They don’t like people like Abraham Lincoln. They kill them. And this man, who had done all of that for India, this man who had given his life and who had mobilized and galvanized four hundred million people for independence so that in 1947 India received its independence, and he became the father of that nation. This same man because he decided that he would not rest until he saw the Muslims and the Hindus together; they had been fighting among themselves, they had been in riots among themselves, and he wanted to see this straight. And one of his own fellow Hindus felt that he was a little too favorable toward the Muslims, felt that he was giving in a little too much toward the Muslims.

And one afternoon, when he was at Birla House, living there with one of the big industrialists for a few days in Delhi, he walked out to his evening prayer meeting. Every evening he had a prayer meeting where hundreds of people came, and he prayed with them. And on his way out there that afternoon, one of his fellow Hindus shot him. And here was a man of nonviolence, falling at the hand of a man of violence. Here was a man of love falling at the hands of a man of hate. This seems the way of history.

And isn’t it significant that he died on the same day that Christ died; it was on a Friday. This is the story of history. But thank God it never stops here. Thank God Good Friday is never the end. And the man who shot Gandhi only shot him into the hearts of humanity. And just as when Abraham Lincoln was shot—mark you, for the same reason that Mahatma Gandhi was shot, that is, the attempt to heal the wounds of a divided nation. When the great leader Abraham Lincoln was shot, Secretary Stanton stood by the body of this leader and said, “Now he belongs to the ages.” And that same thing can be said about Mahatma Gandhi now. He belongs to the ages, and he belongs especially to this age, an age drifting once more to its doom. And he has revealed to us that we must learn to go another way.

Excerpted from “In a Single Garment of Destiny”, published by Beacon Press. All material copyright © Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr.; all material copyright renewed © Coretta Scott King and the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr.

About the Author

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968), Nobel Peace Prize laureate and architect of the nonviolent civil rights movement, was among the twentieth century’s most influential figures. One of the greatest orators in US history, King also authored several books, including Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, and Why We Can’t Wait. His speeches, sermons, and writings are inspirational and timeless. King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968.